Exercises:Mond - Topology - 1

Contents

Section A

Section B

Exercises 6, 7 and 8 make use of the compact-to-Hausdorff theorem

Question 6

Part I

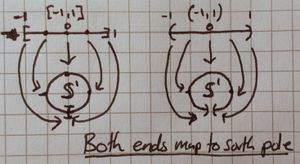

Find a surjective continuous mapping from [ilmath][-1,1]\subset\mathbb{R} [/ilmath] to the unit circle, [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] such that it is injective except for that it sends [ilmath]-1[/ilmath] and [ilmath]1[/ilmath] to the same point in [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath]. Definitions may be explicit or use a picture

Solution

We shall define [ilmath]f:[-1,1]\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] to be such a map:- [ilmath]f:t\mapsto\begin{pmatrix}-\sin(\pi(t+1))\\-\cos(\pi(t+1))\end{pmatrix} [/ilmath], this starts at the point [ilmath](1,0)[/ilmath] and goes anticlockwise around the circle of unit radius once.

- Note: I am not asked to show this is continuous, merely exhibit it.

- Note: The reason for the odd choice of [ilmath]\sin[/ilmath] for the [ilmath]x[/ilmath] coordinate, and the minus signs is because my first choice was [ilmath]f:t\mapsto\begin{pmatrix}\cos(\pi(t+1))\\\sin(\pi(t+1))\end{pmatrix} [/ilmath], however that didn't match up with the picture. The picture goes clockwise from the south pole, this would go anticlockwise from the east pole.

Part 2

Define an equivalence relation on [ilmath][-1,1][/ilmath] by declaring [ilmath]-1\sim 1[/ilmath], use part 1 above and applying the topological version of passing to the quotient to find a continuous bijection: [ilmath](:\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim}\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^1)[/ilmath]

Solution

We wish to apply passing to the quotient. Notice:

- we get [ilmath]\pi:[-1,1]\rightarrow\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim} [/ilmath], [ilmath]\pi:x\mapsto [x][/ilmath] automatically and it is continuous.

- we've already got a map, [ilmath]f[/ilmath], of the form [ilmath](:[-1,1]\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^1)[/ilmath]

In order to use the theorem we must show:

- "[ilmath]f[/ilmath] is constant on the fibres of [ilmath]\pi[/ilmath]", that is:

- [ilmath]\forall x,y\in [-1,1][\pi(x)=\pi(y)\implies f(x)=f(y)][/ilmath]

- Proof:

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in[-1,1][/ilmath] be given

- Suppose [ilmath]\pi(x)\ne\pi(y)[/ilmath], by the nature of implies we do not care about the RHS of the implication, true or false, the implication holds, so we're done

- Suppose [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath], we must show that this means [ilmath]f(x)=f(y)[/ilmath]

- It is easy to see that if [ilmath]x\in(-1,1)\subset\mathbb{R} [/ilmath] then [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)\implies y=x[/ilmath]

- By the nature of [ilmath]f[/ilmath] being a function (only associating an element of the domain with one thing in the codomain) and having [ilmath]y=x[/ilmath] we must have: [ilmath]f(x)=f(y)[/ilmath]

- Suppose [ilmath]x\in\{-1,1\} [/ilmath], it is easy to see that then [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)\implies y\in\{-1,1\}[/ilmath]

- But [ilmath]f(-1)=f(1)[/ilmath] so, whichever the case, [ilmath]f(x)=f(y)[/ilmath]

- It is easy to see that if [ilmath]x\in(-1,1)\subset\mathbb{R} [/ilmath] then [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)\implies y=x[/ilmath]

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in[-1,1][/ilmath] be given

We may now apply the theorem to yield:

- a unique continuous map, [ilmath]\overline{f}:[-1,1]/\sim\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] such that [ilmath]f=\overline{f}\circ\pi[/ilmath]

The question requires us to show this is a bijection, we must show that [ilmath]\newcommand{\fbar}{\bar{f} }\fbar[/ilmath] is both injective and surjective:

- Surjective: [ilmath]\forall y\in \mathbb{S}^1\exists x\in \frac{[-1,1]}{\sim}[\fbar(x)=y][/ilmath]

- There are two ways to do this:

- Note that (from passing to the quotient) that if [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is surjective, then the resulting [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath] is surjective.

- Or the long way of showing the definition of [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath] being a surjection, [ilmath]\forall y\in\mathbb{S}^1\exists x\in\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim}[\fbar(x)=y][/ilmath]

- Let [ilmath]y\in \mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] be given.

- Note that [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is surjective, and [ilmath]f=\fbar\circ\pi[/ilmath], thus [ilmath]\exists p\in[-1,1][/ilmath] such that [ilmath]p=f^{-1}(y)=(\fbar\circ\pi)^{-1}(y)=\pi^{-1}(\fbar^{-1}(y))[/ilmath], thus [ilmath]\pi(p)=\fbar^{-1}(y)[/ilmath]

- Choose [ilmath]x\in[-1,1]/\sim[/ilmath] to be [ilmath]\pi(p)[/ilmath] where [ilmath]p\in[-1,1][/ilmath] exists by surjectivity of [ilmath]f[/ilmath] and is such that [ilmath]f(p)=y[/ilmath]

- Now [ilmath]\fbar(\pi(p))=f(p)[/ilmath] (by definition of [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath]) and [ilmath]f(p)=y[/ilmath], as required.

- Let [ilmath]y\in \mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] be given.

- There are two ways to do this:

- Injective:

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim} [/ilmath] be given. We wish to show that [ilmath]\fbar(x)=\fbar(y)\implies x=y[/ilmath]

- Suppose [ilmath]\fbar(x)\ne\fbar(y)[/ilmath], then we're done, as by the nature of logical implication we do not care about the right hand side.

- Note though, by the definition of [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath] being a function we cannot have [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath] in this case! As a function must map each element of the domain to exactly one thing of the codomain. Anyway!

- Suppose [ilmath]\fbar(x)=\fbar(y)[/ilmath], we must show that in this case we have [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath].

- By surjectivity of [ilmath]\pi:[-1,1]\rightarrow\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim} [/ilmath] we see [ilmath]\exists a\in [-1,1]\big[\pi(a)=x\big][/ilmath] and [ilmath]\exists b\in [-1,1]\big[\pi(b)=y\big][/ilmath]

- Notice now we have [ilmath]\fbar(x)=\fbar(\pi(a))[/ilmath] and that (from the passing to the quotient part of obtaining [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath]) we have [ilmath]f=\fbar\circ\pi[/ilmath], this means:

- [ilmath]\fbar(x)=\fbar(\pi(a))=f(a)[/ilmath], we also have [ilmath]\fbar(y)=\fbar(\pi(b))=f(b)[/ilmath] from the same thoughts, but using [ilmath]y[/ilmath] and [ilmath]b[/ilmath] instead of [ilmath]x[/ilmath] and [ilmath]a[/ilmath].

- In particular: [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath]

- Now we have two cases, [ilmath]a\in(-1,1)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]a\in\{-1,1\} [/ilmath], we shall deal with them separately.

- We have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath], suppose [ilmath]a\in(-1,1)[/ilmath]

- Recall that our very definition of [ilmath]f[/ilmath] required it to be "almost injective", specifically that [ilmath]f\big\vert_{(-1,1)}:(-1,1)\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] was injective (and that it was only "not injective" on the endpoints)

- As [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is "injective in this range" we see that to have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] means [ilmath]a=b[/ilmath] (by injectiveness of [ilmath]f\big\vert_{(-1,1)} [/ilmath])

- As [ilmath]a=b[/ilmath] we see [ilmath]y=\pi(b)=\pi(a)=x[/ilmath] and conclude [ilmath]y=x[/ilmath] - as required.

- We have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath], and this time [ilmath]a\in\{-1,1\} [/ilmath] instead

- Again by definition of [ilmath]f[/ilmath], we recall [ilmath]f(-1)=f(1)[/ilmath] - it maps the endpoints of [ilmath][-1,1][/ilmath] to the same point in [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath].

- To have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] clearly means that [ilmath]b\in\{-1,1\}[/ilmath] (regardless of what value [ilmath]a\in\{-1,1\} [/ilmath] takes)

- But [ilmath]\pi(a)=[a]=\{-1,1\}[/ilmath] and also [ilmath]\pi(b)=[b]=\{-1,1\}[/ilmath]

- So we see [ilmath]y=\pi(b)=\{-1,1\}=\pi(a)=x[/ilmath], explicitly: [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath], as required

- We have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath], suppose [ilmath]a\in(-1,1)[/ilmath]

- We have shown that in either case [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath]

- Notice now we have [ilmath]\fbar(x)=\fbar(\pi(a))[/ilmath] and that (from the passing to the quotient part of obtaining [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath]) we have [ilmath]f=\fbar\circ\pi[/ilmath], this means:

- By surjectivity of [ilmath]\pi:[-1,1]\rightarrow\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim} [/ilmath] we see [ilmath]\exists a\in [-1,1]\big[\pi(a)=x\big][/ilmath] and [ilmath]\exists b\in [-1,1]\big[\pi(b)=y\big][/ilmath]

- Suppose [ilmath]\fbar(x)\ne\fbar(y)[/ilmath], then we're done, as by the nature of logical implication we do not care about the right hand side.

- Since [ilmath]x,y\in\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim}[/ilmath] was arbitrary, we have shown this for all [ilmath]x,y[/ilmath]. The very definition of [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath] being injective.

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim} [/ilmath] be given. We wish to show that [ilmath]\fbar(x)=\fbar(y)\implies x=y[/ilmath]

Thus [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath] is a bijection

Part 3

Show that [ilmath][-1,1]/\sim[/ilmath] is homeomorphic to [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath]

Solution

To apply the "compact-to-Hausdorff theorem" we require:

- A continuous bijection, which we have, namely [ilmath]\fbar:\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim}\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath]

- the domain space, [ilmath]\frac{[-1,1]}{\sim} [/ilmath], to be compact, and

- the codomain space, [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath], to be Hausdorff

We know the image of a compact set is compact, and that closed intervals are compact in [ilmath]\mathbb{R} [/ilmath], thus [ilmath][-1,1]/\sim=\pi([1-,1])[/ilmath] must be compact. We also know [ilmath]\mathbb{R}^2[/ilmath] is Hausdorff and every subspace of a Hausdorff space is Hausdorff, thus [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^1[/ilmath] is Hausdorff.

We apply the theorem:

- [ilmath]\fbar[/ilmath] is a homeomorphism

Question 7

Let [ilmath]D^2[/ilmath] denote the closed unit disk in [ilmath]\mathbb{R}^2[/ilmath] and define an equivalence relation on [ilmath]D^2[/ilmath] by setting [ilmath]x_1\sim x_2[/ilmath] if [ilmath]\Vert x_1\Vert=\Vert x_2\Vert=1[/ilmath] ("collapsing the boundary to a single point"). Show that [ilmath]\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] is homeomorphic to [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] - the sphere.

- Hint: first define a surjection [ilmath](:D^2\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^2)[/ilmath] mapping all of [ilmath]\partial D^2[/ilmath] to the north pole. This may be defined using a good picture or a formula.

Solution

Definitions:

- [ilmath]H[/ilmath] denotes the hemisphere in my picture.

- [ilmath]E:D^2\rightarrow H[/ilmath] is the composition of maps in my diagram that take [ilmath]D^2[/ilmath], double its radius, then embed it in [ilmath]\mathbb{R}^3[/ilmath] then "pop it out" into a hemisphere. We take it as obvious that it is a homeomorphism

- [ilmath]f':H\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath], this is the map in the top picture. It takes the hemisphere and pulls the boundary/rim in (along the blue lines) to the north pole of the red sphere. [ilmath]f'(\partial H)=(0,0,1)\in\mathbb{R}^3[/ilmath], it should be clear that for all [ilmath]x\in H-\partial H[/ilmath] that [ilmath]f'(x)[/ilmath] is intended to be a point on the red sphere and that [ilmath]f'\big\vert_{H-\partial H}[/ilmath] is injective. It is also taken as clear that [ilmath]f'[/ilmath] is surjective

- Note: Click the pictures for a larger version

- [ilmath]\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] and [ilmath]D^2/\sim[/ilmath] denote the quotient space, with this definition we get a canonical projection, [ilmath]\pi:D^2\rightarrow D^2/\sim[/ilmath] given by [ilmath]\pi:x\mapsto [x][/ilmath] where [ilmath][x][/ilmath] denotes the equivalence class of [ilmath]x[/ilmath]

- Lastly, we define [ilmath]f:D^2\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] to be the composition of [ilmath]E[/ilmath] and [ilmath]f'[/ilmath], that is: [ilmath]f:=f'\circ E[/ilmath], meaning [ilmath]f:x\mapsto f'(E(x))[/ilmath]

The situation is shown diagramatically below:

- [ilmath]\xymatrix{ D^2 \ar[d]_\pi \ar[r]^E \ar@/^1.5pc/[rr]^{f:=f'\circ E} & H \ar[r]^{f'} & \mathbb{S}^2 \\ \frac{D^2}{\sim} }[/ilmath]

Outline of the solution:

- We then want apply the passing to the quotient theorem to yield a commutative diagram: [ilmath]\xymatrix{ D^2 \ar[d]_\pi \ar[r]^E \ar@/^1.5pc/[rr]^{f} & H \ar[r]^{f'} & \mathbb{S}^2 \\ \frac{D^2}{\sim} \ar@{.>}[urr]_{\bar{f} } }[/ilmath]

- The commutative diagram part merely means that [ilmath]f=\bar{f}\circ\pi[/ilmath][Note 1]. We get [ilmath]f=\bar{f}\circ\pi[/ilmath] as a result of the passing-to-the-quotient theorem.

- We take this diagram as showing morphisms in the TOP category, meaning all arrows shown represent continuous maps. (Obviously...)

- Lastly, we will show that [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] is a homeomorphism using the compact-to-Hausdorff theorem

Solution body

First we must show the requirements for applying passing to the quotient are satisfied.

- We know already the maps involved are continuous and that [ilmath]\pi[/ilmath] is a quotient map. We only need to show:

- [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is constant on the fibres of [ilmath]\pi[/ilmath], which is equivalent to:

- [ilmath]\forall x,y\in D^2[\pi(x)=\pi(y)\implies f(x)=f(y)][/ilmath]

- [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is constant on the fibres of [ilmath]\pi[/ilmath], which is equivalent to:

- Let us show this remaining condition:

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in D^2[/ilmath] be given.

- Suppose [ilmath]\pi(x)\ne\pi(y)[/ilmath], then by the nature of logical implication the implication is true regardless of [ilmath]f(x)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]f(y)[/ilmath]'s equality. We're done in this case.

- Suppose [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath], we must show that in this case [ilmath]f(x)=y(y)[/ilmath].

- Suppose [ilmath]x\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath] (meaning [ilmath]x\in D^2[/ilmath] but [ilmath]x\notin \partial D^2[/ilmath], ie [ilmath]-[/ilmath] denotes relative complement)

- In this case we must have [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath], as otherwise we'd not have [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath] (for [ilmath]x\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath] we have [ilmath]\pi(x)=[x]=\{x\}[/ilmath], that is that the equivalence classes are singletons. So if [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]\pi(y)=[y]=\{x\}=[x]=\pi(x)[/ilmath]; so [ilmath]y[/ilmath] can only be [ilmath]x[/ilmath])

- If [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath] then by the nature of [ilmath]f[/ilmath] being a function we must have [ilmath]f(x)=f(y)[/ilmath], we're done in this case

- Suppose [ilmath]x\in \partial D^2[/ilmath] (the only case not covered) and [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath], we must show [ilmath]f(x)=f(y)[/ilmath]

- Clearly if [ilmath]x\in\partial D^2[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]y\in\partial D^2[/ilmath].

- [ilmath]E(x)[/ilmath] is mapped to the boundary/rim of [ilmath]H[/ilmath], as is [ilmath]E(y)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]f'(\text{any point on the rim of }H)=(0,0,1)\in\mathbb{R}^3[/ilmath]

- Thus [ilmath]f'(E(x))=f'(E(y))[/ilmath], but [ilmath]f'(E(x))[/ilmath] is the very definition of [ilmath]f(x)[/ilmath], so clearly:

- [ilmath]f(x)=f(y)[/ilmath] as required.

- Clearly if [ilmath]x\in\partial D^2[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\pi(x)=\pi(y)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]y\in\partial D^2[/ilmath].

- Suppose [ilmath]x\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath] (meaning [ilmath]x\in D^2[/ilmath] but [ilmath]x\notin \partial D^2[/ilmath], ie [ilmath]-[/ilmath] denotes relative complement)

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in D^2[/ilmath] be given.

We may now apply the passing to the quotient theorem. This yields:

- A continuous map, [ilmath]\bar{f}:D^2/\sim\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] where [ilmath]f=\bar{f}\circ\pi[/ilmath]

In order to apply the compact-to-Hausdorff theorem and show [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] is a homeomorphism we must show it is continuous and bijective. We already have continuity (as a result of the passing-to-the-quotient theorem), we must show it is bijective.

We must show [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] is both surjective and injective:

- Surjectivity: We can get this from the definition of [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath], recall on the passing to the quotient (function) page that:

- if [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is surjective then [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] (or [ilmath]\tilde{f} [/ilmath] as the induced function is on that page) is surjective also

- I've already done it "the long way" once in this assignment, and I hope it is not frowned upon if I decline to do it again.

- if [ilmath]f[/ilmath] is surjective then [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] (or [ilmath]\tilde{f} [/ilmath] as the induced function is on that page) is surjective also

- Injectivity: This follows a similar to gist as to what we've done already to show we could apply "passing to the quotient" and for the other questions where we've had to show a factored map is injective. As before:

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] be given.

- Suppose [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)\ne\bar{f}(y)[/ilmath] - then by the nature of logical implication we do not care about the RHS and are done regardless of [ilmath]x[/ilmath] and [ilmath]y[/ilmath]'s equality

- Once again I note we must really have [ilmath]x\ne y[/ilmath] as if [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath] then by definition of [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] being a function we must also have [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)=\bar{f}(y)[/ilmath], anyway!

- Suppose that [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)=\bar{f}(y)[/ilmath], we must show that in this case [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath].

- Note that by surjectivity of [ilmath]\pi[/ilmath] that: [ilmath]\exists a\in D^2[\pi(a)=x][/ilmath] and [ilmath]\exists b\in D^2[\pi(b)=y][/ilmath], so [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)=\bar{f}(\pi(a))[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\bar{f}(y)=\bar{f}(\pi(b))[/ilmath], also, as [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] was the result of factoring, we have [ilmath]f=\bar{f}\circ\pi[/ilmath], so we see [ilmath]\bar{f}(\pi(a))=f(a)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\bar{f}(\pi(b))=f(b)[/ilmath], since [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)=\bar{f}(y)[/ilmath] we get [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\bar{f}(\pi(a))=\bar{f}(\pi(b))[/ilmath] also.

- We now have 2 cases, [ilmath]a\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath] and [ilmath]a\in \partial D^2[/ilmath] respectively:

- Suppose [ilmath]a\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath]

- As we have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]b=a[/ilmath], as if [ilmath]b\ne a[/ilmath] then [ilmath]f(b)\ne f(a)[/ilmath], because [ilmath]f\big\vert_{D^2-\partial D^2}:(D^2-\partial D^2)\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] is injective[Note 2] by construction

- If [ilmath]b=a[/ilmath] then [ilmath]y=\pi(b)=\pi(a)=x[/ilmath] so [ilmath]y=x[/ilmath] as required (this is easily recognised as [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath])

- As we have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]b=a[/ilmath], as if [ilmath]b\ne a[/ilmath] then [ilmath]f(b)\ne f(a)[/ilmath], because [ilmath]f\big\vert_{D^2-\partial D^2}:(D^2-\partial D^2)\rightarrow\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] is injective[Note 2] by construction

- Suppose [ilmath]a\in\partial D^2[/ilmath]

- Then to have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]b\in\partial D^2[/ilmath]

- This means [ilmath]a\sim b[/ilmath], and that means [ilmath]\pi(a)=\pi(b)[/ilmath]

- But [ilmath]y=\pi(b)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]x=\pi(a)[/ilmath], so we arrive at: [ilmath]x=\pi(a)=\pi(b)=y[/ilmath], or [ilmath]x=y[/ilmath], as required.

- This means [ilmath]a\sim b[/ilmath], and that means [ilmath]\pi(a)=\pi(b)[/ilmath]

- Then to have [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] we must have [ilmath]b\in\partial D^2[/ilmath]

- Suppose [ilmath]a\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath]

- We now have 2 cases, [ilmath]a\in D^2-\partial D^2[/ilmath] and [ilmath]a\in \partial D^2[/ilmath] respectively:

- Note that by surjectivity of [ilmath]\pi[/ilmath] that: [ilmath]\exists a\in D^2[\pi(a)=x][/ilmath] and [ilmath]\exists b\in D^2[\pi(b)=y][/ilmath], so [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)=\bar{f}(\pi(a))[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\bar{f}(y)=\bar{f}(\pi(b))[/ilmath], also, as [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] was the result of factoring, we have [ilmath]f=\bar{f}\circ\pi[/ilmath], so we see [ilmath]\bar{f}(\pi(a))=f(a)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\bar{f}(\pi(b))=f(b)[/ilmath], since [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)=\bar{f}(y)[/ilmath] we get [ilmath]f(a)=f(b)[/ilmath] and [ilmath]\bar{f}(\pi(a))=\bar{f}(\pi(b))[/ilmath] also.

- Suppose [ilmath]\bar{f}(x)\ne\bar{f}(y)[/ilmath] - then by the nature of logical implication we do not care about the RHS and are done regardless of [ilmath]x[/ilmath] and [ilmath]y[/ilmath]'s equality

- Let [ilmath]x,y\in\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] be given.

We now know [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] is a continuous bijection.

Noting that [ilmath]D^2[/ilmath] is closed and bounded we can apply the Heine–Borel theorem to show [ilmath]D^2[/ilmath] is compact. As [ilmath]\pi:D^2\rightarrow\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] is continuous (see quotient topology for information) we can use "the image of a compact set is compact" to conclude that [ilmath]\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] is compact.

A subspace of a Hausdorff space is a Hausdorff space, as [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] is a topological subspace of [ilmath]\mathbb{R}^3[/ilmath], [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] is Hausdorff.

We may now use the compact-to-Hausdorff theorem (as [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] is a bijective continuous map between a compact space to a Hausdorff space) to show that [ilmath]\bar{f} [/ilmath] is a homeomorphism

As we have found a homeomorphism between [ilmath]\frac{D^2}{\sim} [/ilmath] and [ilmath]\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath] we have shown they are homeomorphic, written:

- [ilmath]\frac{D^2}{\sim}\cong\mathbb{S}^2[/ilmath].

Section C

Notes

- ↑ Technically a diagram is said to commute if all paths through it yield equal compositions, this means that we also require [ilmath]f=f'\circ E[/ilmath], which we already have by definition of [ilmath]f[/ilmath]!

- ↑ Actually:

- [ilmath]f\big\vert_{D^2-\partial D^2}:(D^2-\partial D^2)\rightarrow(\mathbb{S}^2-\{(0,0,1)\}) [/ilmath] is bijective in fact!